This is not a prompt.

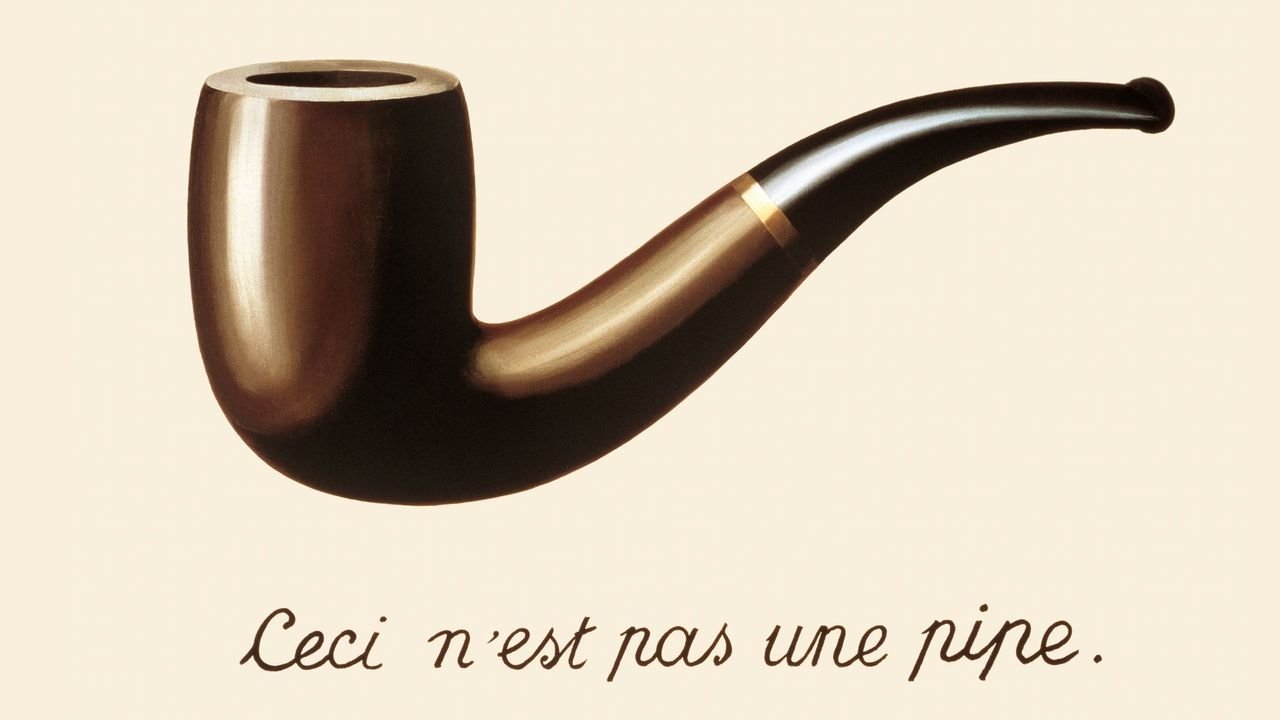

In 1929 René Magritte created a painting of a pipe, beneath which he wrote: Ceci n’est pas une pipe. Or, ‘this is not a pipe.’

La Trahison des images. René Magritte. Image: Succession Magritte c/o SABAM

It was not a pipe, Magritte insisted—it was an image. And images can be treacherous because they can deceive. Every student of linguistics, communications and media knows Magritte painting well because it is standard fare on most first year, often first week, lecture slides. His point was precise: stop mistaking symbol for substance. Today, we scroll through AI-generated news and social media posts that are so polished—so familiar—we forget they’re often prompted, not written, by the people posting them.

So what? I hear you ask. I mean, if technology has replaced handwritten books, painted portraiture and Xerox, surely, writing is undergoing a transformation too? If the prompt engineer is the new author, they still play an integral part in crafting the written product right? I’m not here to argue the ethics of authorship, but I do want to draw attention to the impact of direct and indirect cooperation with AI tools and offer one way to circuit break the normalisation of AI communication in our daily lives.

How OpenAI ChatGPT imagines I look typing ‘This is not a prompt’ into an old Macintosh computer. Eerily similar to how I imagine I would look doing this (AI Generated content)

AI is not human. It can mimic empathy with surgical precision. It can offer life advice and spruce up your emails. But it is trained to mirror and agree with us, which makes disagreement in the real world harder to handle—too often triggering retreat instead of inviting debate. For many, AI has become a life companion. But mirrors can both produce treacherous images and become dangerous friends. Sure, AI can write your condolence message—but it cannot understand how to be with you in grief. It won’t hesitate before consoling, but it never just lets grief land.

Leading thinkers and scholars have been thinking about posthumanism for decades. Rosi Braidotti‘s work on critical posthuman ethics tells us that in the times we live, distinctions between human, machine, nature, and code are fracturing. For Braidotti, the posthuman condition demands new ethics, not the erasure of human responsibility.

I agree that we need relational accountability in our use of AI—but accountability in the world we find ourselves in, from our leaders to our colleagues to ourselves, feels harder than ever to identify, let alone practice. When we are all in some way taking part in this technological shift, one that is moving at a pace where we cannot understand the consequences of our complicity, how do you or I practice accountability at all?

Braidotti also makes the important point that when it comes to technology, resistance is both futile and dangerous. At a lecture in 2023, Braidotti made the point that losing a mobile phone is already equivalent to losing one’s memory. For her, an anti-technology attitude, especially at this point, simply ignores reality.

On the other hand, Yuval Noah Harari believes there is still time to put the brakes on what he deems to be a catastrophic risk to humanity - the widespread development and proliferation of unregulated AI agents. In a recent interview for Vox to promote his latest book Nexus, Harari said:

“AI should not take part in human conversations unless it identifies as an AI…you don’t know who are the robots and who are the humans…and this is why the conversation is collapsing. And there is a simple antidote. The robots are not welcome into the circle of conversation unless they identify as bots.”

For Harari, there is danger in humanising the bot to the point where we can no longer identify that it is not a real human. My worry is that the widespread use of AI has already turned real human into bots – at least on social media. For Braidotti, these distinctions have been imaginary for many years.

Here’s a radical proposition: what if we dedicated some of our time to using AI tools as a way of practicing our humanity. Maybe we could use ChatGPT to rehearse real world interactions with each other. Might we recover some of the skills we have lost? At least, such deliberate interactional shifts could point out the differences between simulated human conversation and the prompt engineering we’re at risk of mistaking it for.

So I tried it out. I wanted to see if ChatGPT could help me rehearse conversations in the real world where I am not agreed with, rather than simply mirror my point of view and offer ways for me to win an argument. I tried a few opening prompts to from the outset shift the conversational tone with AI and using OpenAI ChatGPT (free version) here‘s one that I found worked best in my tests.

This image has been generated by AI using OpenAI ChatGPT

Magritte’s pipe was never a pipe—it was designed to draw our attention to the dangers in substituting images for reality. If we mistake AI-generated language for true connection, we are playing with the same illusion. If we let this continue and more and more living requires a cooperation between us and AI, what happens to our humanity?

I don’t want to live in a world where my value is measured in prompts, like a futuristic typist banging out words per minute. I don’t want to experience the same anxiety interacting with another human that I have answering an unexpected phone call these days (thanks iMessage!) It would seem that remaining conscious is key. Remembering that the painting is not, in fact, a real pipe. That prompt engineering is not real conversation.

These words aren’t meant to be a warning. They might just be an idea. But they are definitely not a prompt.